International spectators of Georgia are increasingly impassioned by a desire to understand Georgian politics and the implications of Georgia’s condition as a ‘post-Soviet’ country. These motivations were partially what moved me to visit Georgia for the first time in 2018. Upon my return this year I began to think about this post-Soviet heritage in more depth, specifically, its implications in the world of art. To what extent has this collective socio-political experience been thedefining feature of Georgian contemporary art?

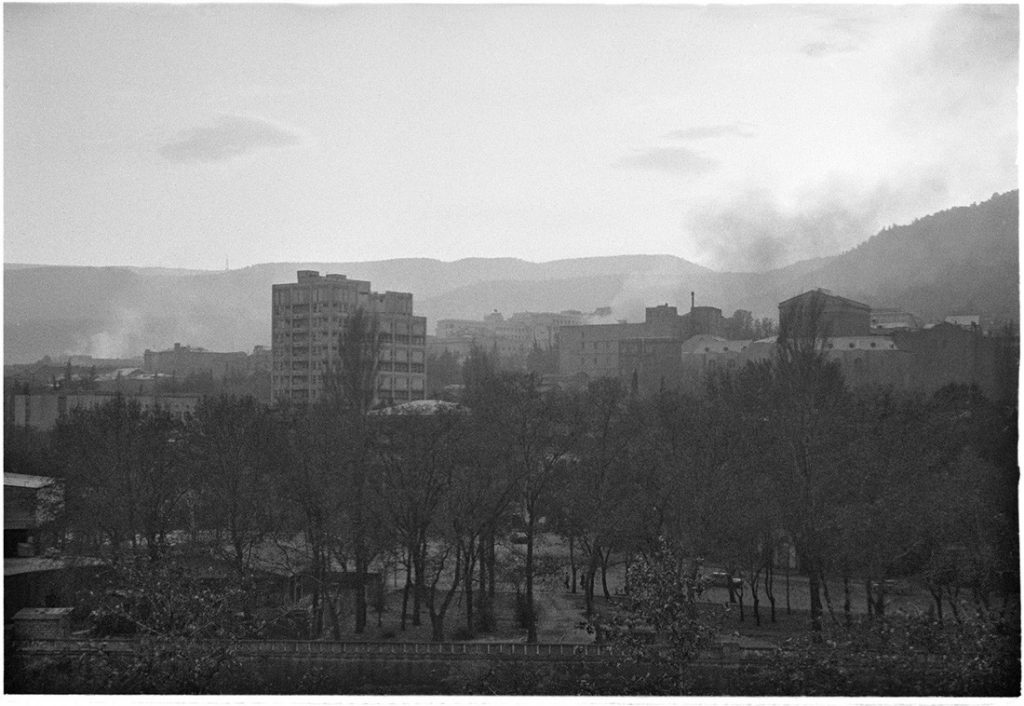

The Georgian non-conformist art scene first began to develop from the 1960s, and it grew illicitly out of Tbilisian artists’ apartments and via impromptu outdoor exhibitions. Artists of this period, such as Otar Chkhartishvili, understandably and obviously had Soviet political concerns as the core inspiration for their work. With the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991, increased freedom for artists, a flood of contact with Western nations, and two decades of ethnic strife and conflict in the Caucasus secured the tone of Georgian art for the foreseeable future. Koka Ramashvili, for instance, made his name through his series of photographs, ‘War from my Window’ (1991-2) and continued his focus on geopolitics into the 2000s (see ‘Pronostic Eventuel’, 1997-2003).

Other artists too, such as Temo Javakhishvili, produced highly politicised art not just in the aftermath of 1991 but continuing well into the new millennium. For example, Javakhishvili’s 1991 performance‘Bul-Bulioni’, in which he read out and then boiled experimental poetry in a broth pot with vegetables, expressed a passionate political frustration. As he said, speaking in 2017, this exhibition demonstrated anger at “being ignored, for instance by the government”. This notion of a lack of a space for artistic expression in Georgia has been a constant theme of Javakhishvili’s work, from ‘Polemics’ (2003) up until his most recent work, ‘Stupid’ (2014), upon which he later elucidated that in an environment where it is difficult to produce, promote and sell art, one might feel as if “you are in a concrete box with just your face on display and all you can do is blink”.

Even much younger artists in Georgia display a keen engagement with socio-political issues relating to Georgia’s legacy as a post-Soviet nation. For instance, the worksof Tamar Berianidze, 26, have focused on her own experiences of forced displacement during the war over South Ossetia in 2008 and issues of memory and geographical disassociation. Similarly, the Erti Gallery, one of the most prominent small galleries in Tbilisi, lists amongst its recent exhibitions, ‘Tomorrow will be yesterday’ (2018); a collaborative exhibition exploring the themes of history, collective memory, forced migration and war.

However, anyone interested in the up and coming art ‘scene’ in Tbilisi can tell you that there is much more to it than ruminations on the post-Soviet condition, political frustration and minority ethnic conflict – and I do not write this article by any means to deny this fact. Events such as Oxygen_Tbilisi_No_Fair(which showcased over 50 Georgian artists and collectives) and the Tbilisi Art Fair2019, both garnered international interest and demonstrated that a new generation of Georgian artists are wholeheartedly transcending regional concerns and creating works which not only reflect on global socio-politics but also those which have little to no political affiliation. This is a welcome breath of fresh air for Tbilisi.

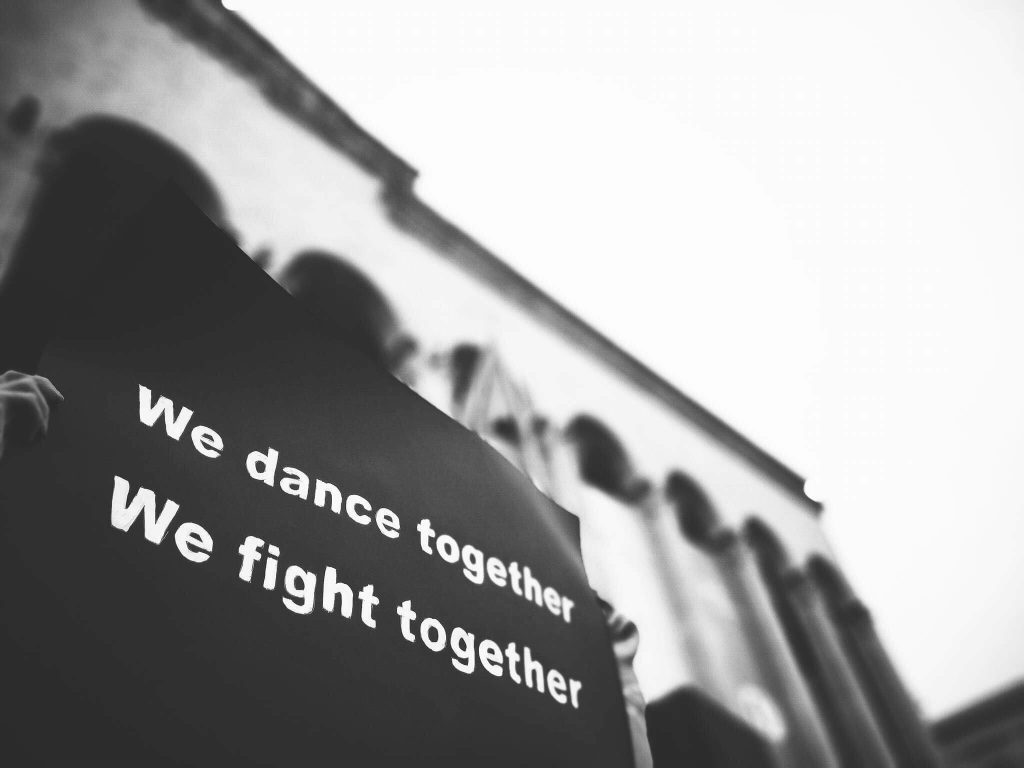

Indeed to a foreign visitor, the city seems to be buzzing with creative energy and nouveau-urban potential. In Georgia, however, it remains impossible to separate this culture from the constant, and typically post-Soviet, threat of aggressive conservatism and political corruption. Most notably in May 2018 the night-club Bassiani – a centre for LGBTQ+ sub-culture and the go-to hangout for Tbilisi cool kids – was raided by the police. Allegedly this was a drugs bust, but more commonly it is believed to have been a show of aggression by the authorities against the alternative creative culture of the city’s younger residents. In light of this event, a re-viewing of Javakhishvili’s 1991 ‘Bul-Bulioni’ depicts Georgian society as a literal ‘melting pot’ containing both radical/progressive and conservative/traditional elements.

Similarly, the presence of numerous small independent galleries, art cafes and underground exhibitions (such as thePatara gallery, situated in an underpass) seem, to foreign visitors, to be the overspill of a thriving art scene. In fact, these spaces represent almost the entirety of the space given over to contemporary art in Tbilisi. The Museum of Modern Art Tbilisiis, notoriously, the private enterprise of artist-cum-egomaniac Zurab Tsereteli and exhibits mostly his own works. Meanwhile, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tbilisiis defiantly operating as a ‘Museum on Call’- which is to say you can request to have the contents of the museum delivered in a briefcase straight to your door. These endeavours are the result of the fact that the Georgian government gives over little to no funding to the arts. Oxygen_Tbilisi_No_Fair 2018 was a privately funded non-commercial event, whilst the Tbilisi Art Fair 2019, one of the few events to receive government funding, saw the pledged amount halve partway through preparations, and then decrease again shortly before the launch. Clearly, whilst the creative scene in Tbilisi exists as such- marginalised, underfunded and threatened- it will be necessarily tied to expressions of political frustration and demands for recognition and creative platforms. We might conclude that in these circumstances making art in Georgia remains a highly-politicised act.