The defining features of musical genres, especially when it comes to “folk” or “traditional” music, are in a constant state of negotiation and prone to blurs and shifts. Previous notions of “local” or “historical” traditions continue to be challenged and interpreted, taking on new meanings and forms. Often mirroring this process is the simultaneous shift in how these practices are researched, recorded, and made available to the public.

These days, a real innovation is taking place in regard to the preservation and popularization of “traditional” music. Newly formed, independent organizations, particularly those with a background in experimental and underground music, have shifted their focuses onto recording, producing, and distributing music that was once the sole consideration of scholars, state institutions, and the small communities that call this music their own. In years previous, music enthusiasts would look to labels like Smithsonian Folkways or other academically affiliated institutions to research and listen to music from different parts of the world. As of 2018, one is more likely to come across LPs, tapes, cassettes, and digital copies of a wide variety of musical traditions, such as the music of Xinjiang province or Sudanese synth and violin recordings, that have been released by independent labels.

These fairly new organizations represent the varying ways in which archival musical examples, overlooked minority cultures, and contemporary field recordings of niche, extremely local musical traditions are being redistributed through online networks directed towards a global audience with a penchant for hearing unfamiliar sounds. It’s this process, referred to by some as “world music 2.0”, that potentially represents one direction to move in regarding the promotion and distribution of “traditional” music in the Caucasus. The growing movement serves as both a critique of the approach of some academic circles and an embracing of DIY (do it yourself) ethic and conventions of underground music scenes. While the movement has lead to many complex discussions and concerns regarding appropriation, misuse and the ethics of musical consumption (succinctly outlined in a piece by the ethnomusicologist David Novak titled The Sublime Frequencies of New Old Media), this article is meant simply as an introduction to the various actors in this ongoing movement and an outline of how a scene has started to take shape here in the Caucasus.

To start with one of the key players in the global DIY ethnographic label scene, take Sublime Frequencies, initially formed in Seattle, Washington, USA, by members of the experimental music group Sun City Girls. The label has over 100 releases on multiple formats, mostly featuring music from Southeast Asia, North and West Africa, and the Middle East. According to their website, the label is focused on releasing sounds captured in “film and video, field recordings, radio and short wave transmissions, international folk and pop music, sound anomalies, and other forms of human and natural expression not documented sufficiently through all channels of academic research, the modern recording industry, media, or corporate foundations.”

Clearly, the project was founded with its own ideology and focus – Sublime Frequencies’ members work to fill what they see to be glaring gaps in the coverage of musical cultures.

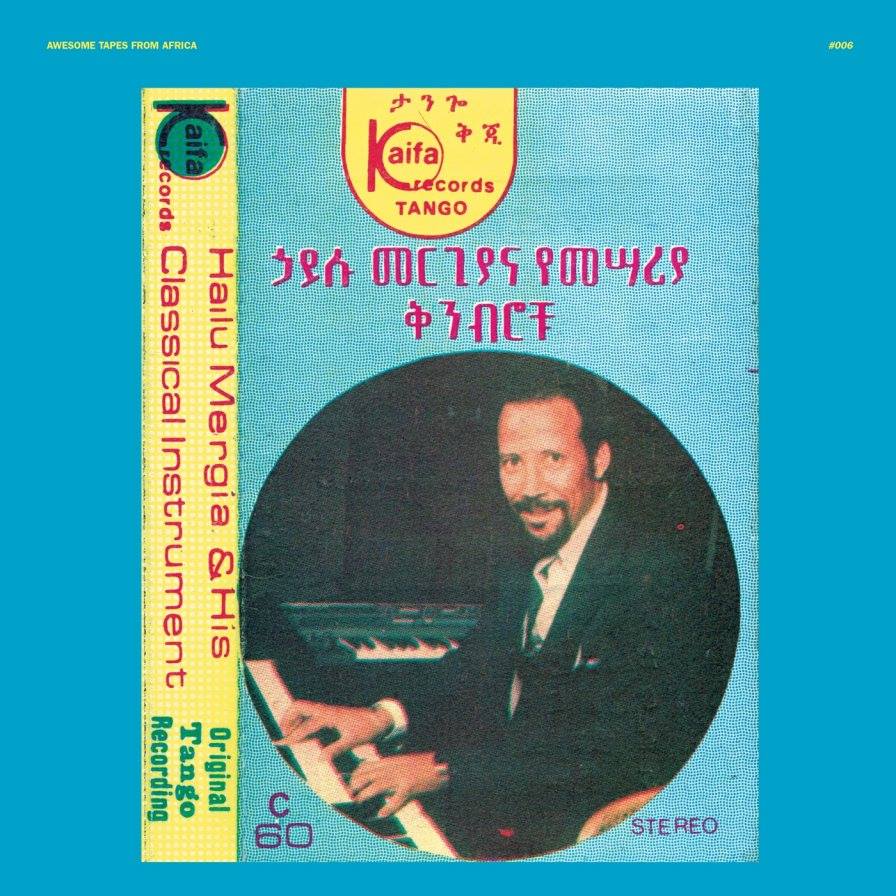

Awesome Tapes from Africa is another popular example, formed in 2006 by Brian Shimkovitz as a means of sharing tapes he had collected in cassette markets while living in West Africa. The website quickly expanded and became a means of re-releasing out of print recordings from African musicians.

According to Shimkovitz, the featured musicians are paid every six months and receive 50% of the profits from each release. In this way, Awesome Tapes from Africa represents a more collaborative approach to releasing local music on a global scale.

Finally, the project Aural Archipelago, described by the project’s founder and sole member Palmer Keen as “part digital archive, part blog,” tackles the immense work of documenting local musical traditions in Indonesia. Traveling throughout the incredibly diverse and scattered islands of the Indonesian archipelago, Keen collaborates with a wide network of musicians in order to “allow audiences (local and foreign) free access to music that is often difficult or impossible to hear otherwise.”

So far, Aural Archipelago has released none of their recordings in a physical format, and instead is focused on a completely open access structure that stresses audio and video examples posted frequently over various forms of social media.

These are just a few examples of the different approaches independent organizations are making towards recording, archiving, distributing, and in a sense, popularizing local musical traditions from different areas and communities of the world. This growing movement coincides with many aspects of globalization and the internet age and raises a series of important questions that we can apply to the Caucasus: 1. How are local musical traditions here being preserved, studied, and promoted? 2. What are some of the issues with the current approaches 3. What are examples of independent projects being implemented in the region, and 4. Are there ways in which music local to the Caucasus region can benefit from these new approaches?

“Traditional” music in the Caucasus is primarily supported, recorded, and archived by state supported structures such as ministries of culture, conservatories, music schools, festivals, and community centers. Embedded within the ideology of many of these institutions are components of nationalism, aspects of the Soviet academic system, political considerations formed during the nation building projects of that system’s collapse, and an ongoing argument of what is considered acceptable or worthy musical culture.

Some of this stems from the long and contested history of the coverage and promotion of musical traditions during the Soviet period. At this time, music was categorized, reformed, and promoted along internal “national” boundaries. Certain musical traditions were supported by the state as representative of each of the Soviet Republics and “peoples”, while others were suppressed in line with different social and political agendas.

In some ways there has been a continuation of this practice in the independent countries of the Caucasus, where there is often common to separate musical traditions across national and ethnic lines. Countries have tended to promote specific traditions and musicians nationally and internationally as being uniquely representative of their nation’s culture.

The primary method for speaking about “traditional” music in Caucasus region is to focus on the promotion and coverage of national musics (for example, polyphonic singing in Georgia, Mugam and Ashiq culture in Azerbaijan, and the duduk in Armenia). Up until recently, most recording and research work has been done by students and professors from conservatories and anthropology programs across the region. These institutions are sponsored by the state, which has a vested interest in promoting specific kinds of traditions and musicians.

The music of say, Armenians in Tbilisi, Georgians in Northwest Azerbaijan, or Molokan in rural Armenia (and countless other examples), has been often overlooked. Not only are many of these traditions outside of the normal interest of the state, there is just such as diversity of musical traditions in the region that it would be impossible to cover them completely with only the staff of small, often underfunded, institutions. There is a clear gap in musical coverage, preservation, and promotion that could filled with the work of independent organizations.

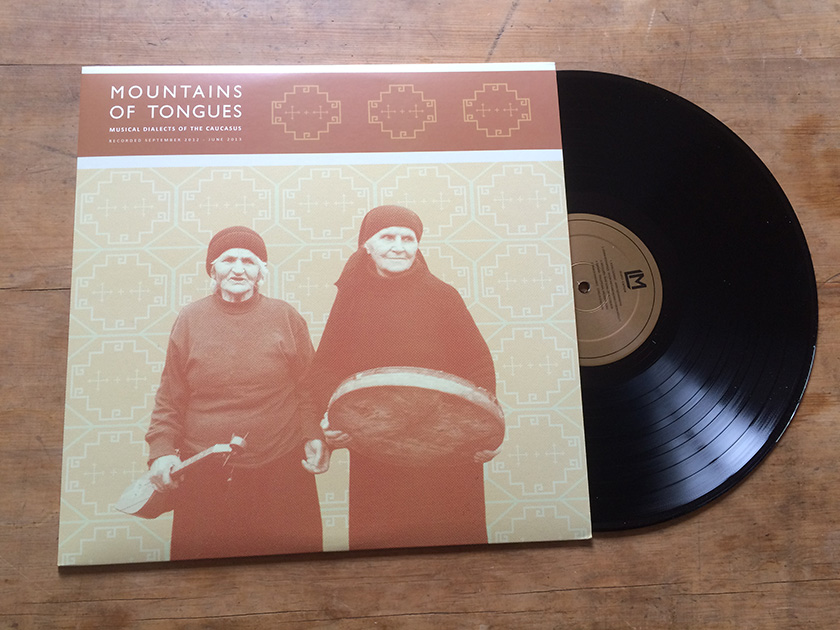

And, as it turns out, there are multiple independent projects based in the Caucasus that have taken new, DIY approaches and applied them to the music of the region. I’m writing this article as the co-founder of one such organization, Mountains of Tongues, which was started in 2012. Mountains of Tongues is dedicated to the preservation of lesser known musical traditions of the Caucasus, particularly those of ethnic, linguistic, and religious minorities.

After years of traveling around the region, meeting, recording, and interviewing musicians, we released an album of our field recordings, Mountains of Tongues: Musical Dialects of the South Caucasus, which features 19 musical examples from all over the South Caucasus.

https://lmduplication.bandcamp.com/track/armenian-and-azerbaijani-kamancheh-medley-sergo-kamalov

Our primary work at the moment is focused on the founding and organization of educational initiatives such as a music journal (Caucasus All Frequency), workshops, and a music festival (Caucasus All Frequency Festival), in order to help expand an understanding of the music of the region and bring together musicians from different backgrounds to exchange knowledge with one another. While there is still an emphasis on conducting field recordings and releasing music into digital circulation, we are trying to also expand the platforms for musical engagement with musicians from the region.

No organization has been more prolific in terms of conducting field recordings and creating digital releases of music in the North Caucasus than Ored Recordings, a DIY ethnographic record label founded by Bulat Khalilov and Timur Kodzoko in their home city of Nalchik, Kabardino-Balkaria. Both of the label’s founders grew up interested in black metal and experimental music, completely alienated from local traditional music which they found to be tasteless and overproduced. After assisting the international DIY film maker Vincent Moon during his travels in the region, the two came to the realization that a new approach should be taken to documenting and releasing local music and decided to form their own project.

Ored Recordings have produced compilations of various Circassian artists as well as Dargin, Chechen, Abkhaz and Abkhaz Pontic Greek musicians. Bulat is also one of the main characters in the film “Bonfires and Stars,” which traces one Moscow electronic musician’s perhaps misguided journey into mixing Circassian folklore into his music.

And finally, the experimental duo Farhad Farzali & Ali Hasanov, who perform under the name Naschkatze, represent another approach to working with music from the Caucasus. Based out of Baku, Farhad and Ali incorporate archival recordings of traditional music from the Caucasus into their own electronic compositions while simultaneously providing releases of previously un-digitized materials from various archives in Azerbaijan.

Focusing on unreleased reel to reel tapes of Azerbaijani soundtrack composers, their label Geschenk Recordings plans to make available for the first time multiple releases of historical compositions.

Currently, there are these few DIY ethnographic/record label projects active in the Caucasus, each with their own approaches. Whether it be music journalism, and educational initiatives, field recording and preservation of endangered musical traditions, or the digitization of undiscovered or unappreciated archival examples, each organization is trying to develop new ways to help foster and preserve local music. The emphasis moving forward should be to present these projects as potential models for new organizations and initiatives, to encourage more and more musicians and music enthusiasts to organize and experiment with these approaches and in the process develop their own. Is anyone releasing materials of music from archives in Tbilisi? Are there independent record labels in Yerevan working to record Armenian and Kurdish music in the surrounding regions? Is anyone curating concert of ethnic minorities in Azerbaijan? (just to name a few possibilities). If not, there is an opportunity here to apply these models across the Caucasus, take note of some of new approaches to the recording, preservation, and promotion of “traditional” music, and to heighten our understandings of the incredibly diverse and multifaceted musical cultures the region has to offer.