It’s obvious to most of us in Tbilisi that the past few years have marked a significant increase in the variety of musical activities and the coverage of the“scene” in Georgia. Local clubs most of all have received near universal recognition and continue to evolve; education centers that move beyond “traditional” conservatory style courses continue to pop up to meet the growing demand for DJ courses, song writing, music production, and a variety of other contemporary subjects, venues suited not just for electronic dance music, but a wide variety of experimental groups, solo artists and projects, have started to host more and more diverse concerts. But there is still room for growth and in many ways musicians in Georgia, especially on the outskirts of the scene, may not have the same advantages as musicians abroad when it comes to access to a wide variety of musical equipment and specialized forms of education.

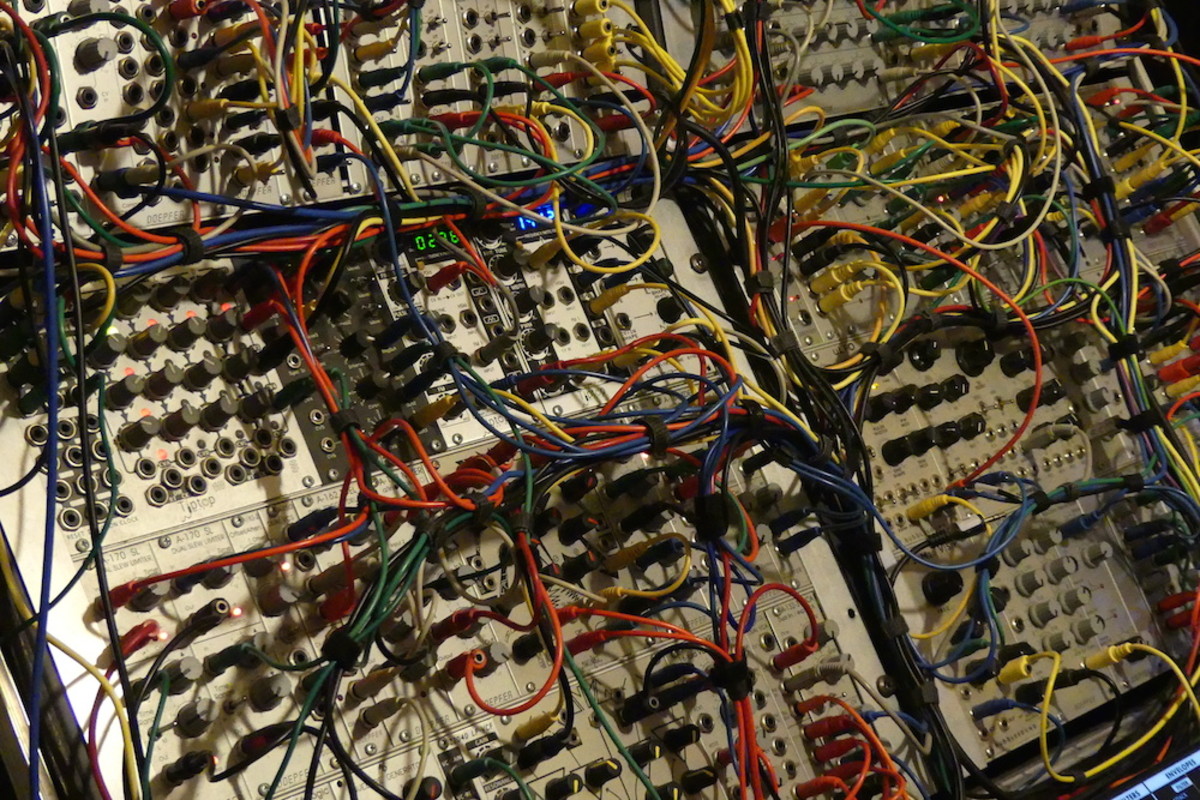

One example of a segment of the musical community that appears to be growing in spite of these challenges is made up individuals interested in performing and experimenting with modular synthesis and its corresponding instruments known as modular synthesizers. For the uninitiated, these instruments often feel like an intimidating and confusing mess of knobs, switches, flashing lights, and tangled patch cables. But for those deeply dedicated or even just beginning to spark their obsession with the practice of modular synthesis, these machines provide a limitless amount of freedom, experimentation, and potential. Essentially, a modular synthesizer is made up of a series of specialized modules in the shape of small metal panels, each with their own functions and mechanisms, that can be patched together in a near infinite variety of combinations. Musicians often customize their own modular rigs, picking and choosing from the creations of wide variety of small scale and often independent module makers that exist within the global scene, piecing together a completely unique instrument that reflects their personal musical aesthetics and inclinations.

Modular synthesis has been experiencing a renaissance of sorts over the past decade, with builders, musicians, and entire genres expanding around the rapid construction of, and experimentation with, these exciting machines. Shops and small scale workshops dedicated solely to the construction and sales of custom modules have popped up around the US and Europe and tours and showcases of musicians focused on the practice of modular synthesis have become more and more common. Many artists, such as Don Gero, work as modular builders and also use these components in new and unexpected ways, merging them with acoustic instruments so that they serve as controllers or modifiers.

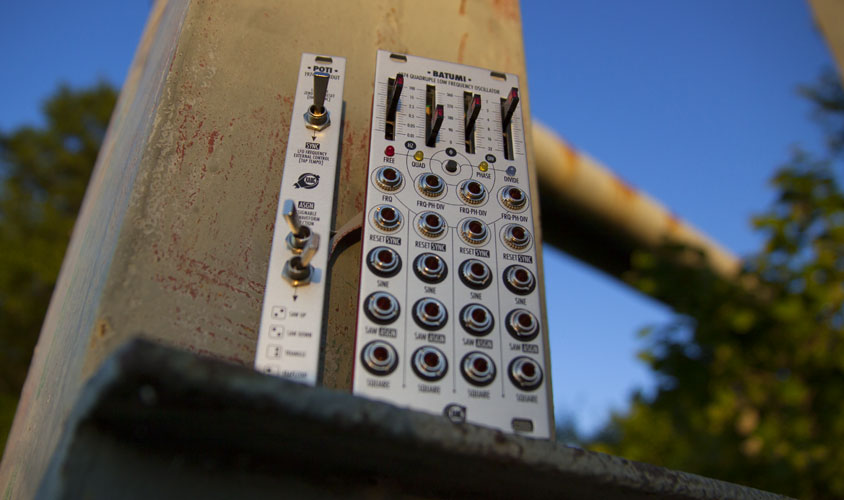

The situation is quite different in Georgia. Unfortunately, until very recently musicians in Georgia have been extremely limited in terms of the access, capital, and kinds of education that are often times needed in order to foster a local modular synth community. Ironically, the Polish company Xaoc Devices has created a very popular module (a “quadruple low frequency oscillator” to be exact) named after the city of Batumi and a corresponding expansion module called Poti, but next to no one in the country owns or has access to either. But, thanks to the inspiration and efforts of a few members of the musical community, interest in these machine shows signs of accelerated growth as more and more people have begun studying, building, and performing using modular – there is real potential here, an opportunity to watch and listen to a scene that may be about to come into its own.

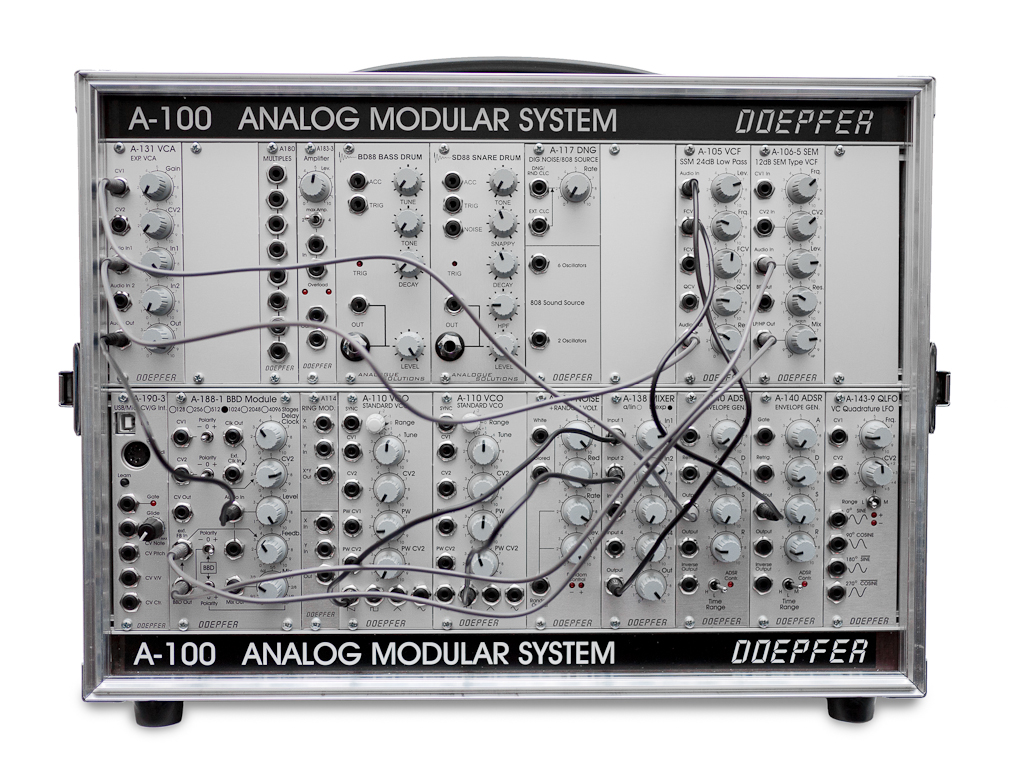

The following are short interviews, one with the head of the Creative Education Studio Nastia Sartania, who was the first to make the Doepfer A-100 (a classic model modular synthesizer) part of the curriculum for a special course on synthesis, and a second with the teacher and creator of said course, the experimental musician and educator Tornike Margvelashvili (who performs under the name Mess_Montage), who has become one of the main proponents of modular synthesis in Georgia. These conversations are meant to shed light on an emerging musical practice in Georgia that will hopefully continue to grow, innovate, and expand.

BW: What inspired you to make the Doepfer a part of the curriculum at Creative Education Studio?

NS: For me, inspiration always comes from people; when I see someone very excited and really believing in something, I can always tell it’s going to work! Tornike Margvelashvili is like any other tutor at CES, totally in love with his profession and enjoys every bit of sound there is to hear in life. So one day he came to me and mentioned how much he would love to have a modular synthesizer for his program Synth 101. There was so much passion in his explanation of what a difference it would make for his course and what a good impact it could have on what at the time was a practically non-existent Georgian community of synthesis lovers. It only took him about 5 minutes to convince me to get this machine and give it a try.

BW: How have you seen the program progress since it’s start?

NS: Before the Doepfer A-100, Tornike’s course was called Synthesis 101 and lasted only 2 months. It was more based on theoretical aspects. Since the instrument’s introduction we have renamed the course: it’s called Synthesis and Sound Design and last 3 months. I think the course has become more musical and more practical. Now that we have the Doepfer, Tornike has been holding public workshops regularly and tries to make the device more accessible for CES students and alumni who haven’t taken his classes. After his workshops and masterclasses more and more people are becoming familiar with the concept of modular synthesis and are less and less scared of it. They are beginning to understand it and fall in love with it.

BW: What got you interested in modular initially?

TM: I think the idea of exploring modular synthesis came to me naturally as I followed the urge to have a really customized instrument for live electronic performances. Something that could be flexible, all inclusive, and interactive at the same time. This type of electronic instrument can be very unique and personal, not just physically and sonically, but also in terms of composition processes and concepts. You are free to set your own limitations, your own formulas to explore your own personal world in a fun way; I kind of look at it like a physical analog computer – you put your own rules, processes, mindsets, traditions and it can spit out hours of unique sonic paintings.

BW: How do you feel about the current state of modular in Georgia? What role does education play in the process of popularizing and experimenting with modular synthesis?

TM: In most cases, education is the shortcut to achieving the results you’re looking for. I think a well rounded education should consist of some mix of theory, practice, listening, analysis, and creative thinking; every rule you learn you should also be ready to break it and make it your own. A school should create a safe environment for experimenting by providing time, encouragement and making gear available. It should also serve as a place where like minded people can gather and exchange ideas, so that all this learning becomes a social thing. If there had been a class in modular synthesis a few years ago when I got interested in all this, it would have saved me lots of time and effort.

BW: What do you think about the future of modular synthesis in the region? What are some of the hurdles individuals and communities need pass through before it becomes a widely available and accessible practice?

First off, I know there are some real struggles. These include a steep learning curve and having to choose from thousands of amazing modules. Prices can also be very prohibitive. It’s also hard to get hold of a huge variety of modules here in Tbilisi which certainly hinders development of the field. Fortunately, some companies, such as Erica Synths, ExpertSleepers, Pittsburgh Modular, have expressed their support both for me and the whole community and I’m thankful for that and hope there is more support to come.

Overall, I imagine the future of modular synthesis in our region unfolding in a very interesting manner. If we inject all of our unique history, our mindsets, our sonic specialties into these power-full ‘living machines’ they will spit out super exciting results. And that’s the process that I’m looking for as an artist as well: trying to make my approach really honest, to pair it with the power of modular and a mind for exploration, and to see what comes out of it.